Labour’s approach to immigration in government

Immigration was a major practical and political headache for Rishi Sunak’s Conservative government. After pledging to reduce immigration levels, the numbers had tripled to record levels. Rising numbers of asylum seekers crossing the Channel clearly showed that high-profile pledges to “stop the boats” had failed. The Sunak government lost confidence on control, on compassion and on competence with every shade of opinion.

The Starmer government inherits both the challenges of high overall immigration numbers and of uncontrolled asylum flows across the Channel at a time of low trust in governments and politicians. However, immigration was a much lower priority issue for most Labour voters than for Conservative and Reform voters – with Labour supporters holding more liberal or pragmatic ‘balancer’ of immigration.

The riots and disorder across the UK during the summer also saw a heightened debate about the role of immigration in these outbreaks of xenophobic and racist violence and how to respond to it.

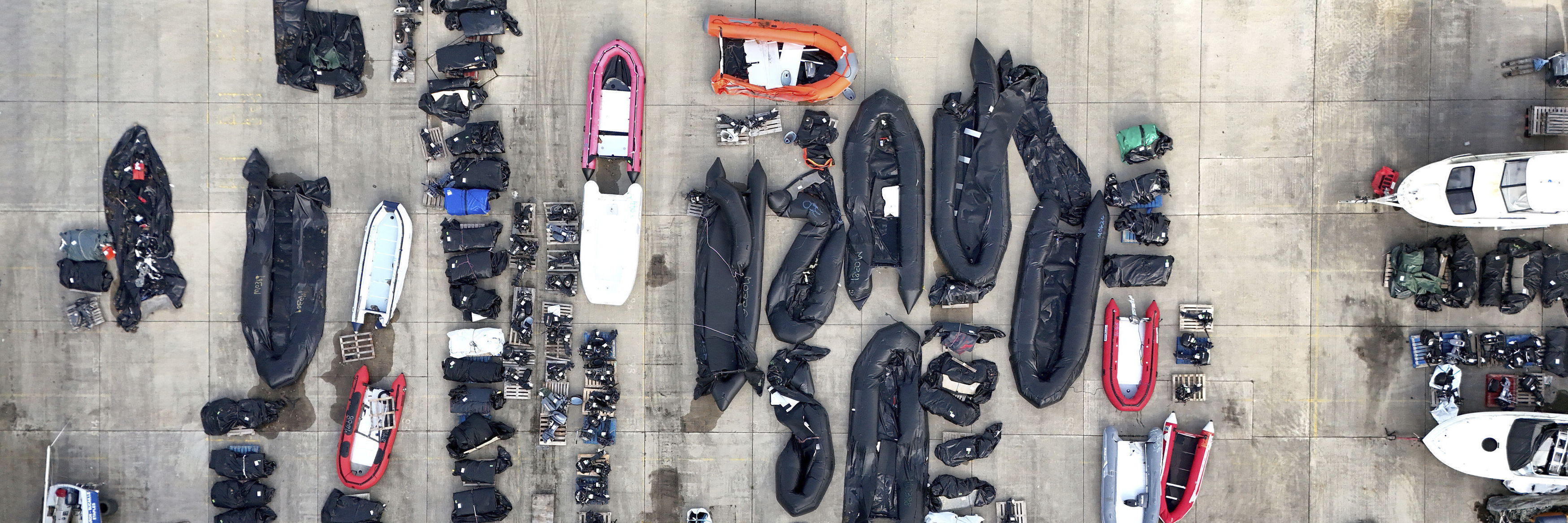

Asylum and Channel Crossings

Labour’s political message on asylum sought to blend a commitment to a “tolerant and compassionate” country with a “controlled and managed” asylum system and “strong borders”.

Labour made two major liberal policy commitments: to scrap the outgoing government’s Rwanda scheme – and to process the asylum cases of those who had arrived in the UK without permission. The outgoing government had passed several laws proposing to permanently bar unauthorised entrants from the asylum system – but, in practice, had no way to deliver this. Even if the Rwanda partnership had become operational, it could not have taken more than 1-2% of the 65,000 asylum seekers who the government had pledged to remove. So, the outgoing government would have had no lawful alternative to processing asylum claims – but delayed acknowledging this before the election, so it could challenge Labour’s policy as a de facto “amnesty”.

Labour framed its proposals primarily as workable and cost-effective alternatives to a chaotic inheritance. The funds saved from the “wasteful” migration partnership would be invested in a new Border Security Command. Processing asylum cases – granting refugee status to tens of thousands of asylum seekers – would get a grip on the escalating backlog of cases, so saving millions of pounds a day on the temporary accommodation bill. A new returns and enforcement unit with 1000 staff would remove those whose claims failed to safe countries - with a commitment to work upstream on humanitarian crises.

Thus, the Starmer government intended a three-pronged approach on asylum: projecting a tough approach to smuggling gangs; fixing the asylum system at home to make decisions effectively and reduce escalating costs; and seeking to deepen multilateral cooperation to manage asylum flows more effectively. Yet Labour retreated from emphasising multilateral ambitions once the Conservatives caricatured a willingness to talk as a secret plan to sign up to EU-wide asylum quotas.

The emphasis is now more strongly on national and multilateral action to “smash the gangs”. Starmer has also made his sustained commitment to the European Convention on Human Rights clear, where the UK Conservatives are debating reform, derogation or departure. The Labour government’s position is officially agnostic on off-shore processing – where, unlike the Rwanda scheme, the UK retains oversight and responsibility, as long as these are compatible with international law. But there is no active pursuit of such proposals, given doubts about their purpose, practicality or cost.

The medium-term question for the Starmer government is when or whether it will return to its ambitions to negotiate new arrangements, whether on family reunion, or a broader ‘routes and returns’ deal with France, including opening new legal routes to claim asylum in the UK.

Work, study and the numbers question

The major UK parties had converged on a post-Brexit system where ending freedom of movement was combined with a liberal regime for work and study, increasing non-EU migration significantly. Commonwealth countries, particularly India and Nigeria, have played a key role in this shift, with Indian nationals making up 21% of total immigration to the UK in 2023 and Nigerian nationals contributing about 12%.

Labour’s manifesto contained little detail on immigration for work and study. With net migration at record levels, the party stated that the overall level of net migration would come down – with more attention to linking domestic skills and immigration policies. Labour made no new proposals on any particular visa routes, either restrictive or liberal.

The new government will exceed expectations by reducing immigration levels. This is primarily because the current level – net 680,000 – is exceptionally high for exceptional reasons. The new government maintained late policy changes by the last government – removing the eligibility of dependents of graduate students and care workers. There is little public awareness of this coming decrease: just 12% of people expect immigration levels to fall in the next 12 months, with majorities expecting record levels to continue or to increase again.

By 2025, net migration to the UK will be around half of the current level – though probably above the 250,000 net migration average of the first two decades of the century. It remains to be seen if the new government can use this to reframe the media and public politics of immigration.

The Conservative Opposition is set to again re-propose a ceiling of 100,000 for net migration – the old target that the Conservative governments never came close to delivering in office. The right’s emerging idea from leadership frontrunner Robert Jenrick is a legal cap to make this level mandatory. Keir Starmer and Home Secretary Yvette Cooper do not support a specific net migration target nor a legal cap. The government’s 2025 challenge may be whether and how to use the breathing space of lower numbers to shift the policy goal and framework for political accountability.

Violence, disorder and “legitimate concerns” about immigration

Britain saw its worst outbreak of public disorder for over a decade this summer. The killing of three young girls in Southport saw an outpouring of public grief. The effort to target asylum seekers and Muslim as a violent retaliation against groups with no connection to the shocking crime. The violence spread at pace – mostly as a series of one-off flashpoints in over thirty locations. Fewer than five thousand people were involved, though with wider participation online.

The targeting of asylum seekers, Muslims and ethnic minorities made these riots the most concerted outbreaks of racist violence in Britain for decades. Around fifteen thousand people took part in widely celebrated counter-protests, mobilised in response to online threats of widespread vigilante violence across the UK.

There was a contested debate about the role of migration underpinning the disorder. Did violence bubble up because politicians were too afraid to debate immigration, as right-of-centre commentators claimed, or were they stoked up by the incendiary language of those who talk about little else?

The UK government’s initial focus was to be visibly tough on violence, disorder and hatred. Rapid and visible prosecutions played a role in restoring order.

Keir Starmer recognised the racist motive for much of the violence – and was clear that government policy would not be influenced by riots and disorder

Most people strongly opposed the violence and disorder. But 85% disapproval of violence leaves 7% of people willing to say they supported it – including 2% who were strongly supportive. That is a large enough toxic minority to not just give moral oxygen to the disorder – but to spread fear well beyond those places where mayhem broke out.

In talking about legitimate concerns, it is essential to be clear about what is illegitimate too.

There are legitimate concerns about immigration – but the violence and disorder of the summer of 2024 was an orgy of illegitimate concerns.

Properly understood, legitimate concerns are a two-way street. There are ‘legitimate concerns’ about how a democracy handles the pressures and gains of migration and social change - and also about keeping racism, prejudice and violence out of our democratic debate. A legitimate debate about migration and integration would address both sets of concerns. In a democratic debate, there are different views about immigration policy and politics. So ‘legitimate concerns’ are about a right to have your voice heard, not a right to get everything you want.

The long-term challenge is how the government could now go on to address the causes of disorder by putting in place the missing foundations for a strategy for community cohesion and tackling prejudice in the UK.

About

Sunder Katwala is the director of British Future, a non-partisan think-tank and charity working on issues of identity and immigration, race and integration, including extenisve research into public attitudes. He has previously worked in research, journalism and pubishing, including as General Secretary of the Fabian Society from 2003-2011, as a leader writer and internet editor for the Observer newspaper, research director of The Foreign Policy Centre, and commissioning editor for politics and economics for the publisher Macmillan. He is the author of the book 'How to be a patriot'.

The opinions and statements of the guest author expressed in the article do not necessarily reflect the position of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.